Processes

Using the Command-Line

COP-3402

Table of Contents

The process abstraction

A process is a running program.

Running programs

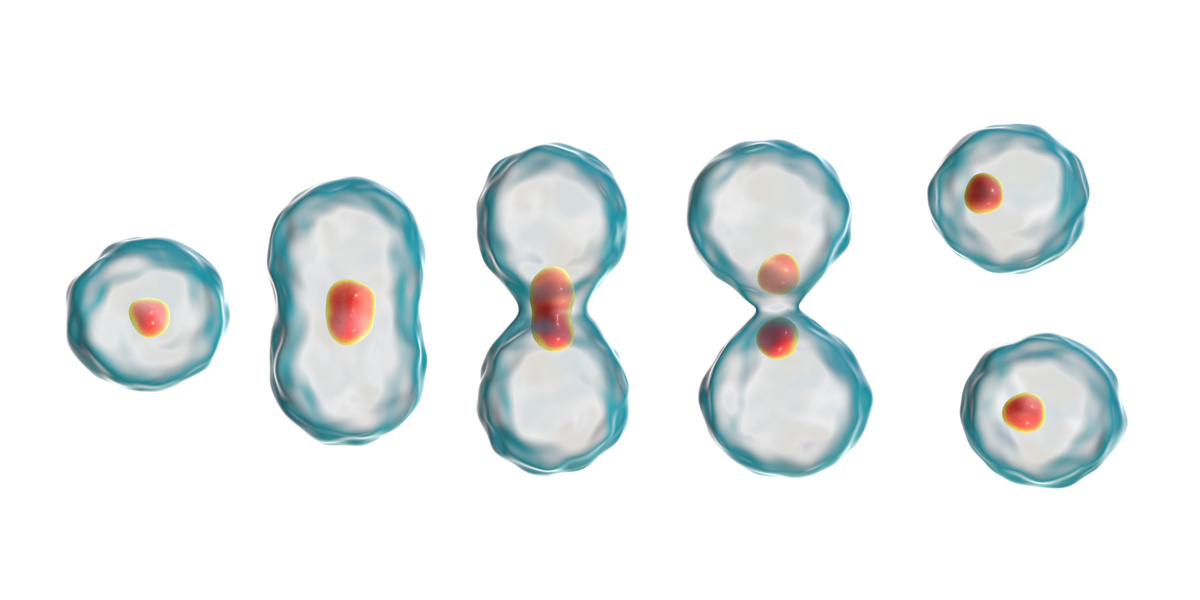

Diagram

- Program: bytes on disk, machine code

- Load into memory

- Jump to first instruction

- Program runs!

Problem: we want to run many programs, but we only have one CPU.

What can we do?

There are several solutions.

- Batch processing

- Add more CPUs

- Distributed programming

- Virtualize the entire machine

- Time sharing (the one we'll use in this class)

Time sharing

Virtualize the CPU: give programs the illustion of exclusive CPU access

Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces

- Remember how we talked about the kernel idealizes hardware?

- One thing modern OSes do is virtualize the CPU.

Many running programs

Diagram

- Many virtual CPUs

- One physical CPU

- Kernel mediates the sharing

Processes "freeze" the state of the CPU

- Process control block

- Process ID (unique ID for all running programs)

- Saves register values

- Saves current working directory

- Saves pointer to its memory

- File descriptors

- etc.

UNIX process creation

Copy existing process with fork()

Replace program code with new program with exec()

We will work with process creation syscalls when we get to systems programming.

What about the first process?

- Single initial process (init)

- Many variations (sysv init rc system, systemd)

- e.g., runs /usr/bin/login program among other things

- Running processes form a tree

Diagram

- init process

- process tree

- process creation

View running in this bash session

ps

View all processes on the system

ps aux

View the process tree

ps axjf

Running programs

Type the file name of the executable, hit <enter>

ls

We've already been creating lots of processes from programs such as ls and mkdir.

Find out more about bash syntax.

Command-line arguments

Additional space-deliminted strings are arguments passed to the program for processing. They are handled however the program likes, although there are conventions to their format (man 3 getopt).

ls ./ ../

There are special characters bash recognizes that aren't part of arguments, such as pipes |. We will look at these more when we get to redirection and advanced processes.

There are ways to handle escaping special characters, e.g., \| and including spaces in a single-argument, e.g., with double-quotes.

Where are programs?

UNIX convention: the PATH environment variable

echo $PATH

Why have a PATH?

Finding a programs path

The which program does the lookup for you

which ls

which which

Programs not in the path

hello # program not found

Why does running hello by itself fail? I compiled it. The program is there.

This is one reason for using the dot path, when we want to specify a path to the file, but do not want to have to type out the absolute path to the current working directory.

./hello

Commands that aren't programs

which cd # nothing returned

cd is a builtin command that bash recognizes

How do I run a program that I named cd?

Quick quiz

How do I run a program that I named cd?

Give the path to the program, e.g.,

./cd

Standard I/O

UNIX convention

Every process is given three open files when it runs:

- standard input (stdin)

- standard output (stdout)

- standard error (stderr)

man 3 stdio

"At program startup, three text streams are predefined and need not be opened explicitly: standard input (for reading conventional input), standard output (for writing conventional output), and standard error (for writing diagnostic output)."

On process creation, the parent process's stdio files are inherited.

- Why standard I/O?

- Why separate stdout and stderr?

One reason, I assume, is related to UNIX's interactive design: running a program from the shell means there is already input and output (the terminal).

Standard I/O is also used for the UNIX philosophy of chaining multiple programs together.

You'll see this discussed more in tonight's reading for homework.

Where does standard output/error go?

When running in bash: the terminal itself

echo "hello, world!"

Where does standard in come from?

When running in bash: the terminal itself again

cat # Typing is sent to the cat program's standard in

cat reads a file from stdin and writes it to stdout.

Mark end of input with Ctrl-D

Use Ctrl-D (ascii EOT character) on an empty line to mark the end of file input

The program is waiting for input from stdin, which is the terminal.

An example with grep

grep "hello" # Typing is sent to the cat program's standard in

grep reads a file from stdin and writes out lines that contain a given string.

Don't forget to use Ctrl-D if inputting the stdin file from the command-line.

Waiting for stadnard input is why programs that expect input stop and wait when run from bash.

Redirection

We can use bash to change (redirect) where stdio goes to and comes from.

Redirecting stdio to files

| File | Suffix |

|---|---|

| stdin | < infile |

| stdout | > outfile |

| stderr | 2> errfile |

Example with cat

cat < hello.c

What does cat do?

What does cat < infile do?

How does this differ from running cat infile?

- With

cat < infile, the shell opens the program and cat runs with an existing program open - With

cat infile, the cat program reads the filename and opens the file. - The output is the same in both cases (since the file is the same).

Example with grep

grep define < /usr/include/stdio.h

What does grep do?

What does this program do then?

Example of input and output

grep define < /usr/include/stdio.h > grepresults

What does this do? How can I view grepresults?

Example of error

grep define < /root > grepresults # The error message is printed to console

Redirecting stderr

grep define < /root > grepresults 2> greperror # The error message is saved to greperror

Redirect stdout/stderr to the same file

grep define < /root > grepresults 2>&1

2>&1 means redirect stderr (file 2) to file 1 (stdout). Must place this after the redirect of stdout > grepresults (otherwise it will just use the original stdout.